In a world where we struggle to smile and have peace amidst the harsh reality, comics can, undoubtedly, offer a haven. In collaboration with Comics Culture Collective, Kolkata Centre for Creativity is hosting Comics in Bengal, a one-of-a-kind, captivating exhibition from 9 February to 9 March 2024 at KCC. The exhibition would shed light on the evolution of Bengali comics from its inception in the 1920s to the present day. The wide array of exhibits, including reproduction of rare newspaper strips, magazines, comic books, and some original artworks, will be on display, giving the audience a comprehensive idea about the dissemination of the genre and how it made its way to the popular imagination of the readers, especially from the 1960s onwards. The display would aim to celebrate the creativity, innovation, and artistry that have shaped the comic culture in Bengal. Comics in Bengal is not just an exhibition; it is also a tribute to the brilliant minds behind these masterpieces, namely comic book illustrators including Narayan Debnath, Prafulla Chandra Lahiri, also known as Kafi Khan / P.C.L. / Piciel, Mayukh Chowdhury, Sailya Chakraborty, Sufi, Pratul Bandhopadhyay, and Tushar Chatterjee who honed their skills through regular publications in Bengali periodicals like Mouchak, Nabakallol, Suktara, Sandesh, and Kishore Bharati, among others.

***

“A vaunt this vile abuse of picture page!”

That is what Wordsworth had remarked about picture books – arguably the earliest form of comics. The world has advanced a lot since then, and the likes of DC and Marvel have taken the world by storm with their comic book heroes and superhuman strength. However, the middle-class Bengali household seems to have stuck to the views of the great poet. A teen charmed by the extraordinary abilities of Superman or Spiderman still has to bear numerous taunts when caught reading a comic book.

While Western comics often showcase intricate plots and character development against the backdrop of Western cultural norms and settings, Indian comics offer a refreshing departure, inviting readers into a world where folklore, spirituality, and everyday life intertwine seamlessly. Here, the gods and goddesses of ancient epics coexist with ordinary individuals, their stories interwoven with tales of fun and wit amidst mundanity.

Handa Bhoda by Narayan Debnath. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

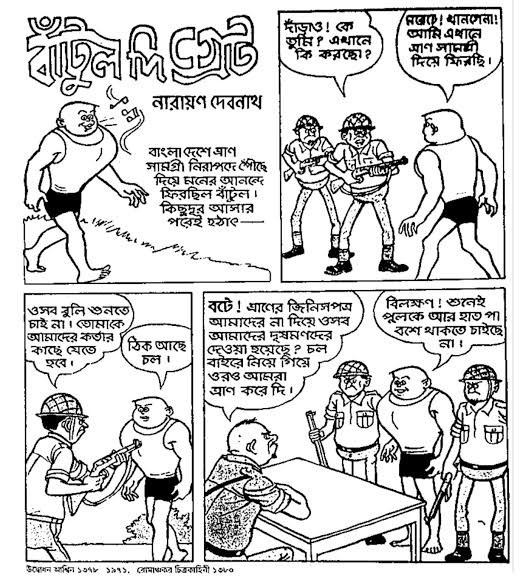

Interestingly enough, among the conventional ‘Bhadraloks’, arose a hero. It was Narayan Debnath who revolutionised the comic culture in Bengal. The likes of Handa Bhonda, Bantul the Great and Nonte Fonte resonated with middle-class Bengalis. Their trivial, funny acts and mischievous adventures were a great source of entertainment. Unlike the comic book characters of the West, these characters were ordinary people to whom the Bengalis could relate. Moreover, the familiar setting of a Mofussil or a boarding school was something that the Bengalis were familiar with. These comics initially started out as strips in children’s monthly magazines, like Shuktara and were sketched in black ink. Coloured comics arrived much later, with Bantul the Great being the first to arrive in hues. However, it wasn’t until the 21st century that multiple colours were used to fill up the grayscale world of Bengali comics.

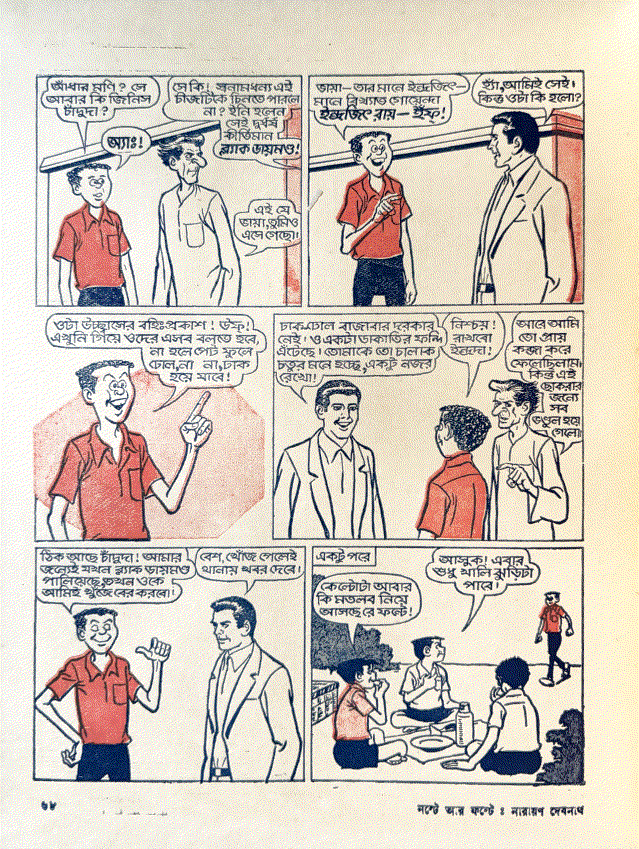

Glimpse from Nonte Fonte by Narayan Debnath, Sharodiya Kishore Bharati (1980). Credits: KCC and Comics Culture Collective

Thus, Bengal got its own comic heroes – who didn’t always have a batarang up their sleeves but were passionate about the Kolkata Derby. However, when looked at closely, these simple characters and their world reveal much more than what meets the eye.

Bantul is portrayed as a mighty superhuman in Bantul the Great by Narayan Debnath. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

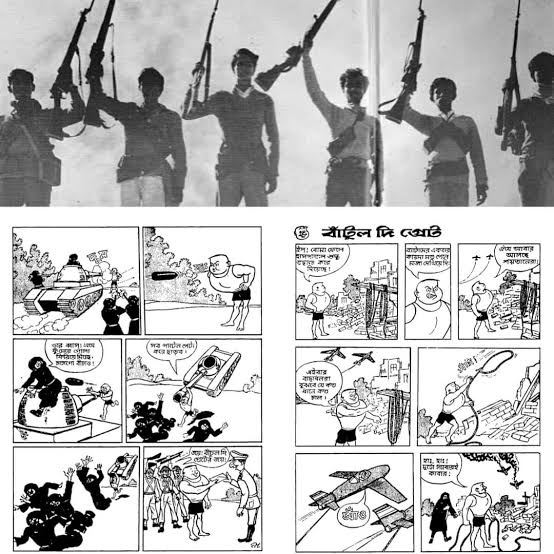

Take, for example, the character of Bantul. This small-town teenage character with sturdy shoulders but childlike simplicity is portrayed as a mighty superhuman being who can destroy anything and everything. He becomes indestructible in nature when used as a propaganda tool during the conflicts in 1971. Bullets are shown to bounce off of him, and missiles from tanks do him no harm. Further, he is shown stealing Pakistani tanks with ease and defeating several regiments of Pakistani forces singlehandedly. Thus, the everyday Bantul becomes a vassal of aggressive nationalism and paints a picture of a false sense of indestructibility in the reader’s mind.

The everyday Bantul becomes a vassal of nationalism. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Other noticeable traits are strikingly similar across all the universes of the Bengali comic world. One that would top the list is the absence of a woman protagonist. There isn’t even a side character who is a female. Even if a woman exists in comic universes, her characterisation is passive and asexual. It is always the man who has all the fun, sometimes of theft and deceit, while at other times crimes like bank robberies, and is never held accountable for his mistakes. Not for once is a woman dealt with in the same manner. In a way, one could argue that the comics portray a man-child in the adult!

Furthermore, Bengali comics could be more diverse. They need more characters which have an origin in the state. Even in terms of portrayed religious groups, one finds little diversity. Funnily enough, only when there are mentions of ghosts in the Bantul universe do we see Mamdobhoot(s), believed to be ghosts of Muslims.

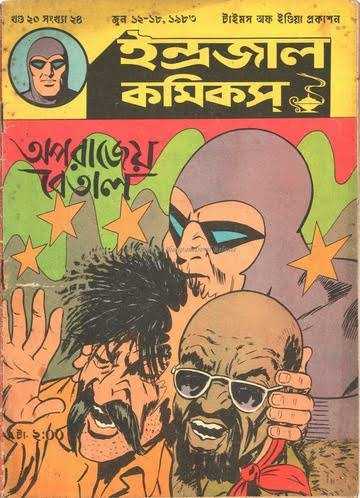

Phantom or Aranyadeb in the cover of Indrajal Comics of 1983. Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Besides these home-grown comic titles, The Times of India Group launched Indrajal Comics back in the 1960s (which met with an abrupt end in the 1990s), under whose banner was translated into Bengali, various English comics such as ‘Phantom’, ‘Mandrake’ and ‘Flash Gordon’. Later, ‘Tintin’ and ‘Asterix’ were published in Bengali translation. These foreign comics also got a Bengali makeover in certain aspects when subjected to translation. For example, Snowy (from Tintin) was renamed ‘Kuttush’, and Panoramix (from Asterix) was renamed Eta-Sheta Mix.

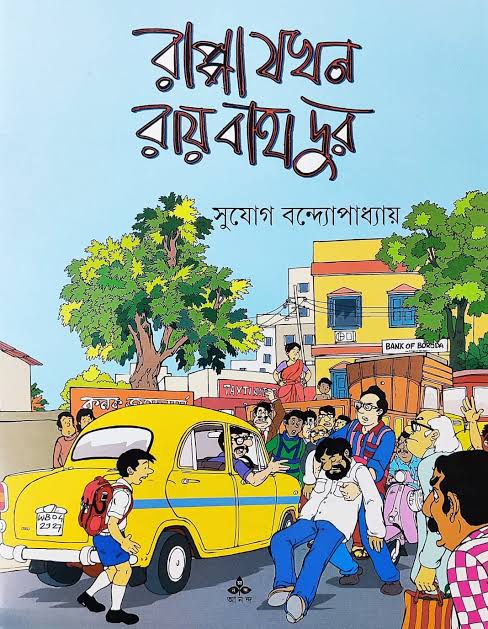

The death of Narayan Debnath seemed like a symbolic death of the comic in Bengal. With reissues of Handa Bhonda, Nonte Fonte and Bantul the Great being published nowadays - that too in English - the Bengali comic world seems to have taken a big hit. However, not all is lost. Sujog Bandyopadhyay seems to have taken over the job of donning the hero’s cape with his Rappa Roy series of comic strips. While the great Debnath limited his comic art to mere sketches of black ink on paper, Bandyopadhyay has made the Bengali comic more vibrant and engaging, making even the littlest details pop using digital art mediums. Besides this, the comic rendition of Dr Shanku, Feluda, Kakababu and others with detailed environments and gripping storylines seem to have put the Bengali comic back on track.

Rappa Roy by Sujog Bandopadhyay, Ananda Publishers, 2014. Credits: Wikipedia

Do not miss out on this chance to encounter fascinating characters literally hanging from the walls of the Kolkata Centre for Creativity till the ninth of March and engage with narratives that resonate with the heart and soul of a culture steeped in tradition yet constantly evolving!

Author bio

Shrutideep Majumder is a student of Jadavpur University, currently pursuing a bachelor's degree in History. An ardent follower of pop culture, he likes to attend music events and fests, spend time in an old bookstore, or go record hunting.