The exhibition celebrates the great artistic genius and extraordinary inventiveness of F.N. Souza (c. 1924–2002). Along with M.F. Husain and S.H. Raza, Souza co-founded the historic Progressive Artists' Group (PAG) in 1947 and was one of the seminal figures in the formation of modern Indian art after Independence. The exhibition features rarely seen drawings and chemical alterations from the final decades of his life, along with a handful of archival documents relating to that period—particularly his relationship with Srimati Lal and her family in Kolkata. Some of these documents also reveal Souza as a fine poet and writer.

The Goan-born artist, who lost his father in childhood, grew up in Bombay as an ailing boy raised by his mother, struggling against poverty. He studied at the JJ School of Art, from which he was expelled due to his participation in Gandhi's Quit India Movement. He was also briefly associated with the Communist Party of India (CPI). Souza was recognized early for both his artistic talent and rebellious spirit. By the late 1940s, he was already well-known in Bombay's artistic circles. An influential figurative painter who, during the heyday of postwar abstraction, called himself a realist, Souza developed a highly individualistic modernist style—marked by an assimilation of elements from diverse sources, both high and low, Asian and Western. Although he left India in 1949 and spent the rest of his life in the West—first in England and later in New York—Souza always identified himself as an Indian artist, shaped by his Christian Portuguese-Goan heritage and sensibilities rooted in the openness and plurality of Indian culture.

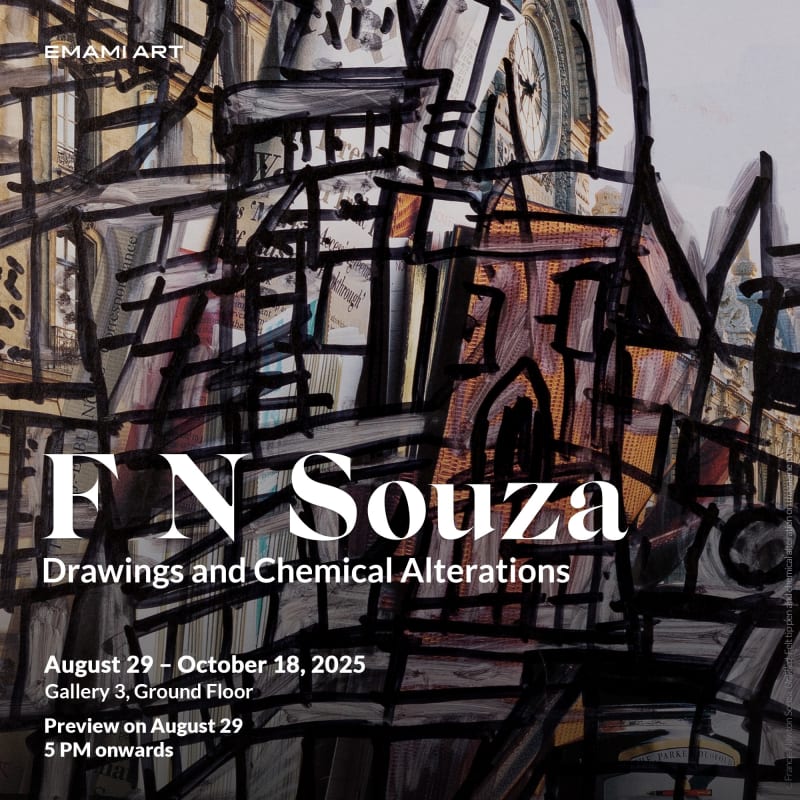

The works on display from the 1980s and '90s showcase Souza's remarkable mastery of chemical alteration – an unconventional medium he developed following a chance discovery. In 1966, Souza was struck by the way his wife's spilled nail polish remover caused the printed images of a magazine to dissolve. Fascinated by the effect, he transformed the accident into a unique artistic technique. By manipulating magazine prints with various solvents, including floor cleaners and turpentine, he altered their colours and forms, allowing his own drawings and writings to enter dialogue with the published content still visible beneath the chemically transformed surface. He coined this medium "painting without paint" during a time of severe financial hardship. His wife, Barbara Zinkant, wrote: "The medium saved on the price of oil and canvases and used up a lot of old porn magazines in the apartment." While his early experiments were simple, the work gradually became more complex and layered over time.

Souza was primarily a painter of women. His unabashedly erotic representations of female nudes—like those of many great painters before and after him, including Modigliani, Matisse, and Picasso—are often shaped by the force of male desire and projection. Despite this, his works are far from pornographic. Unlike the seductive models of pin-up magazines, designed with the singular aim of arousal, endlessly repetitive yet unfulfilled, and an effort to go beyond the realm of image and reality, Souza's women never stray from the realm of art, revealing a masterful experimentation with human form. Many of his drawings, with their exaggerations and distortions, confront and even assault the viewer's eye. Like Picasso—his most admired and deeply explored artist—Souza portrayed women not as pleasing subjects, but as suffering machines, the contested sites of love and law, monstrosity and sex.

A passionate lover, a fierce critic of cultural chauvinism, puritanism and religious dogmatism, and a great proponent of free will, Souza often worked on magazine paper, including pornographic publications. With bold, hurried, and agitated lines and brushstrokes, he transformed the mass-produced glossy paper surfaces into aesthetically charged spaces of eroticism and vitality. Theoretically, we can link his figurative artistic practice to the idea of the rehabilitation of the sensible—an effort to reassert the power of love and other vital human emotions in an age where technology and the culture industries increasingly control our feelings.

- Arkaprava Bose