Somnath Hore is known as an artist with a singular focus on human suffering. He saw suffering not as an ontological fact of existence, but as the outcome of an unjust social system we have built and continue to perpetuate. This meant that it could be changed, and to him, the solution lay in socialist political action. Early in his life, he joined the Communist Party to be a part of this process. But while trying to do this he soon realized two things. One, art guided by the Party can degenerate into propaganda and the production of art can be reduced into an unthinking mechanical process. Two, that to keep emotions alive and intense, and the message fresh, one had to innovate. In art, he realized, one had to change even to remain the same. So he adopted, mastered and extended available mediums, and developed new ones. The white on white prints made by pouring paper pulp into matrixes prepared from moulds made from clay or wax surfaces, and the singular sculptures made by cutting, joining, and hand modelling of thin wax sheets, and then made permanent by casting using the lost wax process were two of his last and more personal innovations.

Of the two, sculpture, which he preferred to call bronzes, came last. He began doing sculptures in 1974, the year I joined Kala Bhavana as a student. I vividly remember him working on a little sculpture of a braying donkey seven or eight inches in size. In those days we often encountered small packs of donkeys on the campus, and occasionally heard them bray. Furthermore, Somnath Hore often represented animals as companions of human victims and as fellow sufferers. So it was not surprising that one of his first sculptures, if not the very first, should be a sympathetic response to the ungainly call of a modest animal.

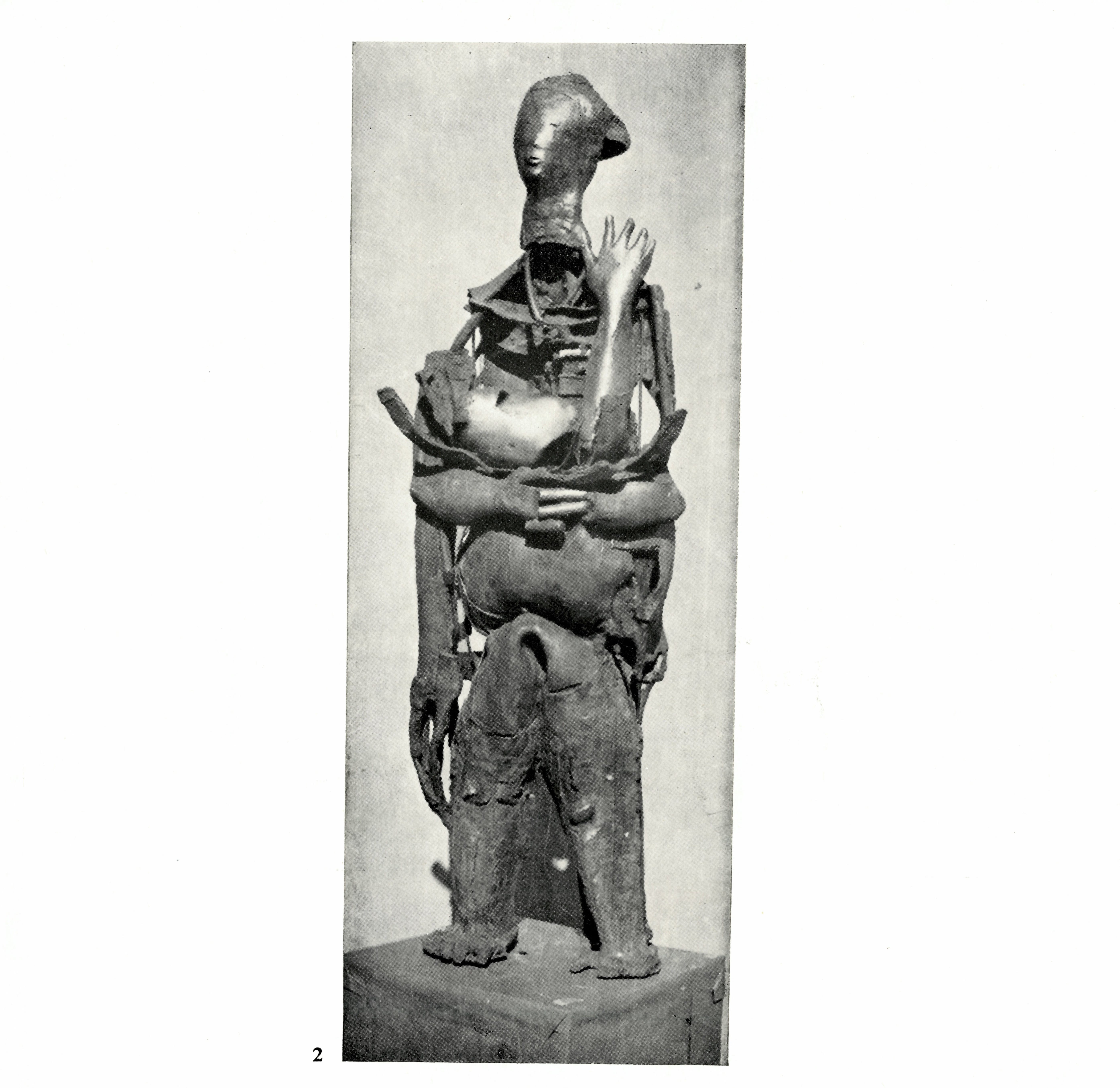

Following this, he made a standing figure, a little larger than the small donkey. The work he did after these first efforts was considerably larger and certainly more ambitious. It showed a woman with her chest blasted, yet standing with her head held high, cradling a baby in her arms with one of its hands raised high—reaching up in a gesture of freedom, of hope. The upper part of her body is like the remains of a battered house, walls torn apart, the skeletal structure exposed, parts unhinged and dangling. What was once solid is made hollow, what was once whole is precariously held together. In contrast, although her legs are composed of mangled sheets, her feet-apart stance suggests stability; and her head, whole, calm and held high suggests determination and invincibility. This is the image of a stoic and undefeated mother and her child, who rising out from her ruined body symbolizes new life.

We know the context of its making from Somnath Hore’s own account. He began it soon after the fall of Saigon in 1975 and the end of the long-drawn Vietnam War and it took him nearly two years to complete it. Vietnam was on his mind since the first student protest in Calcutta in early 1947 in support of Vietnam’s anticolonial movement under the communists. With the American decision to intervene in the affairs of countries ‘threatened’ by communism it turned into a brutal ideological war, and became a matter of concern for Somnath Hore. ‘I had fostered Vietnam within me for many years,’ he later wrote. ‘Reading everyday news about that difficult struggle I often felt frustrated. When that struggle of 29 long years ended in total victory, I did the most important bronze [sculpture] of my life, the Vietnamese Mother.’[i]

Somnath Hore, Mother with Child, Bronze, 1977

Measuring 40 inches in height, it was the most successful among his larger works, and certainly a very important one. But the importance of this work to Somnath Hore, however, was not merely artistic. Badly battered but victorious Vietnam was a living proof of his deepest ideological avowal, a moment of his hope coming true. While the representation of the victims of an unjust social system and their suffering was his constant theme two of his early projects were the documentation of the Tebhaga or sharecroppers’ movement (1946) and the Tea Garden workers’ struggle (1947). These were protests that gave him hope but they were not wholly successful. The Vietnamese victory was decisive and, therefore, the sculpture was of utmost importance to him.

Looking at the sculpture, two other images come to mind. The first David Brunett’s 1972 photo of a Vietnamese mother running with her fatally wounded child documenting the disastrous effect of the American Napalm bombing of Vietnam. This sculpture is a reversal of that image. The second image comes from a written testament. Looking back at his early life Somnath Hore had noted: ‘In the December of 1935 I lost my father and my mother became a widow. My mother was 30, with five children. I the eldest was 14, the twins younger to me were 10, then two sisters, one 6 and the other one-and-a-half-year-old. I intensely realized the blow my mother received as a woman in her full-blown youth after I grew up. Five children: and one of the twins was congenitally and completely insane. Until the age of 20 she had to protect him from varied attacks of neighbours. He died at 24. I have no measure of her suffering. For 72 years, mother bore her suffering determinedly. She had no complaints about her children, neither expectations. She only wished that they be happy in their own ways.’[ii]

His mother, stoic and courageous as the young Vietnamese Mother in his sculpture, probably died while he was working on the sculpture. And her memory, we might assume, is also behind his image commemorating the Vietnamese victory.

As we have noted this sculpture was a long time in the making. It was finally completed around October 1977. Janak Jhankar Narzary who was working on an essay on modern Indian sculpture for Marg had come down from Baroda and wanted to photograph the sculpture. It was brought out and we saw it in its final form and admired it. The patina was yet to be done and so it was left in a common studio. But soon afterward the sculpture was stolen from the studio and was never recovered. Somnath Hore was so pained by its loss he did not do any more sculpture while he was in Kala Bhavan and returned to sculpting only after he retired in 1983.

Somnath Hore’s Vietnamese Mother also reminds us of another sculpture, Picasso’s Man with a Lamb. The two are completely different in subject matter, size and technique, and Picasso’s man is not battered like Somnath Hore’s mother. But made in 1943 during the German occupation of France, Picasso’s sculpture is also an image of stoic determination and hope. The man and the lamb, like the mother and child, invokes an ancient bonding, and together they invoke a composite image of the strong and gentle. Picasso gifted it to be installed in the market square in Vallauris. Wonder where Somnath Hore would have liked to place his sculpture had it not been lost.

[i] Somnath Hore, Kshatachinta, Bhangan, Debabasha, Kolkata 2019, p.26.

[ii] Ibid, p.9.

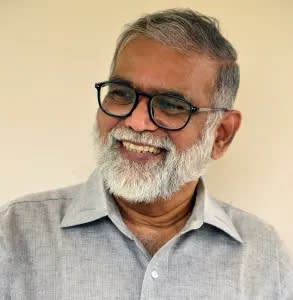

R Siva Kumar is a Professor of Art History at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. Among his extensive contribution to the field of modern Indian art, he has curated and authored accompanying publications for Santiniketan: The Making of a Contextual Modernism, KG Subramanyan: A Retrospective, A Ramachandran: A Retrospective and The Last Harvest: Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore. He co-curated and co-authored Benodebehari Mukherjee: A Centenary Retrospective Exhibition. He edited and introduced the Rabindra Chitravali: Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore. He wrote seminal books on Abanindranath Tagore and Gaganendranath Tagore, which along with Ravindra Chitravali were published by Pratikshan.