"With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people's lives, creating expectations, making friends – all these emotional entanglements come upon the disengagement that follows. Photographers, like myself, deal with people. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away?"

[Shahidul Alam, The Tide Will Turn, p. 108]

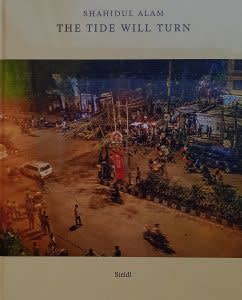

In his book, The Tide Will Turn, Published by Steidl in 2019 in Germany, these concerns pulsate through the practice of Shahidul Alam, a photographer, journalist, activist and writer. The book takes us on a journey with him – to the streets of Dhaka, to the refugee camps of Teknaf, to the flooded lands of Patenga, to the illicit construction sites at Kualalampur, to Bangladesh Photographic society or Charukala Institute, to collapsed garment factories, to the house of parliament or an orphanage in Adabor Market, to Rupnagar, Comilla, Jamalpur, to the Chittagong Hill Tracts, to Dhanmondi, to Shahbag Square, to National Press Club, and finally, to Keraniganj Jail.

Shahidul Alam, The Tide Will Turn, published by Steidl, Germany, 2019 (183 pages, 110 illustrations, ISBN: 978-3-95829-693-0)

Meanwhile, regimes change. Power finds a way of playing its game. People suffer, often in silence. Sometimes, acute endurance erupts in fits of resistance. Retaliation is never far away. Voices get censored. In the grand scheme of things, life goes on. Still, there are stories to be told. Urgently. Dearly. Shahidul Alam's accounts of the 'nameless, faceless' people of Bangladesh, like clenched fists, are raised against the systemic erasure and silence of history. Yet, they remain to be stories of love and loss, of dreams and despair.

After the customary editor's note and a preface acknowledging the unsaid, the book unfolds in three chapters, ending with two letters.

On Prison:

On 29th July 2018, two young school students named Abdul Karim Rajib and Dia Khanam Meem were run over by a speeding bus that injured eleven more. Their classmates witnessed the incident. The apathetic response of the state sparked fury among the schoolchildren. Over the months that followed, the young students protested against the dangerous condition of the roads. Shahidul, inspired by students' spirit and improvised forms of resistance, engaged actively with the movement. His photographs witnessed these children, still too young to take to the streets, to learn the strategies of organizing, or to lose faith in democracy. They proved it possible to bring order and safety to Dhaka's streets with scarce resources. His journalism exposed how Police took arms against the children and tortured them physically to restore chaos.

On 5th August 2018, after his Al Zazeera interview aired worldwide where he commented on these issues, Alam was arrested from his home, and after about a week of custodial torture, was sent to Keraniganj prison.

The book's first chapter illustrates his days in Keraniganj jail, built on barren land, where one can still see the horizon and the changing seasons; prison dormitories are named after Bangladesh's flowers and rivers. Alam creates a near-cinematic portrayal of his sparrows in cardboard boxes and his fellow prisoners in stuffed chambers, their songs and prayers, their cats and their little acts of kindness.

On Stories:

The second chapter offers a glimpse into the history of photography in post-independence Bangladesh and the stories from its margins. It insists that the image repertoire of a young nation should be built by its own artists and not by visiting artists on paid assignments. According to Alam, as international media struggled to shed its preconceived notions around a developing, third-world country; Bangladeshi photojournalists risked their lives, recording reality. Unfortunately, much of it went unnoticed.

Alam's photographic practice has been influenced by the documentary tendencies of his predecessors like Rashid Talukdar, Manzoor Alam beg, Anwar Hossain, and Bijon Sarkar at the Bangladesh Photographic Society; and shaped by his experiences with the people of Bangladesh. Journalism, activism, and photography intertwined in his visual language, and his lucid political position grounded it. Here we see a reflection of his vision.

"I have been trying for so many years to tell the stories of absence." he writes.

but

Whose stories are they?

Alam follows the trail of Kalpana Chakma, among many others, who disappeared one night. An indigenous activist from the Chittagong hill tracts, Kalpana led the Hill Women's Federation. On 12th June 1996, Kalpana had allegedly been abducted at gunpoint by lieutenant Ferdous, who disappeared from the public eye as well. One has the right to wonder if the two disappearances have been of the same nature while they belonged, at least technically, on two different sides of occupation.

Ferdousi Priobhashini struggled for the dignity of women who bore the brunt of a man's war. When the Pakistani army had to leave Bangladesh, the women raped by their soldiers faced a new kind of trauma. Society was not yet ready to accept the survivors as easily as it could embrace the murdered ones. The state efforts for Biranganas (as always, pretty names are in plenty in all countries for all kinds of rape survivors) fell short inevitably. Ferdousi, a survivor herself, carved a path for them as she carved branches and twigs to make art.

Hazera Baegum remembered to smile. "She cries too, but not because of the gang rapes or the beatings or the many years she has spent on Bangladesh's street picking through garbage and struggling as a sex worker. She cries when she remembers that a man from an NGO had refused to work with her because she was a sex worker." Alam recalls.

Her story could have ended here on a sympathetic note, but it goes on with a ten-page-long photographic tribute to her work, defiance, and smile. Hazera Baegum runs an orphanage for abandoned children near Adabor market. Her children receive expensive education, for which she has to work round-the-clock raising funds. They play, study, and love the mother that could not bear biological children.

This, perhaps, is what separates Alam from too many of his contemporaries.

However, he is not alone. Penny Tweedie, a freelance photographer, was covering the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Without a paid assignment, Penny had to stay close to the common people, those who fought, who struggled, who survived, who got killed, who sheltered her, fed her, and gave her 'the ultimate photo op for a photojournalist on a low budget’. She refused to shoot these people as victims of war. The very few photographs she took were blinding sights of resilience. Instead of publishing them to promote her career, she gave them to Drik, a picture library and a photographic agency founded by Shahidul Alam in 1989.

On Hope:

The third chapter on politics records gory accounts of violence by a state against its people, the horror of fundamentalism, and the shrewd killings of capitalism. It also pursues the hopes and dreams of Bangladeshi migrant workers to faraway lands of Dubai, Malaysia as well as the garment factories in Dhaka that employed hundreds of workers migrating from the villages. Some hoped to buy a piece of land, send money home, or arrange a marriage – a better life to look forward to. However, the long working hours, the scarcity of food and sleep, the harsh and often illicit working conditions barely helped the cause. Meanwhile, the traders of labour and labourers made a fortune. Some others also hoped for a better world. Adivasi activists, independent journalists, and bloggers who dared to raise their voices against a broken system were killed, tortured, or made to disappear. The attempts to silence the critics of the state, the capitalist economy, or religious fundamentalism knew no mercy. However, the young nation seems to have people on its side. A rickshaw puller who refuses to charge fellow patriots for their rides, or the people who gather at the Shahbag Square to protest against war crimes and offer public funerals for their beloved martyrs, and those who continue to resist, knowing the consequences of speaking truth to power – echo that The Tide Will Turn. For, in times like these, hope is an act of rebellion.

The book ends on this note, with two letters exchanged between Shahidul Alam and his friend, fellow activist, and author Arundhati Roy, after his imprisonment in 2018. They express how little is different between Dhaka and New Delhi. How prisons are filled with artists, writers, and students in both cities. They end with words of stubborn, and perhaps unreasonable, hope.

“Fortunately, we are an irredeemably untidy people. And hopefully we will stand up to them in our diverse and untidy ways.” Roy writes from India.

“The case still hangs over my head and the threat of bail being withdrawn is the threat they hope will silence my tongue, my pen, and my camera. But the ink in our pens still runs. The keyboards still clatter. At 1/125 of a second, the shutter still clicks.” Alam responds from Bangladesh.

For more information about us you can visit emamiart website.

Sarmistha Bose is an artist with a leaning for literature. She studied Mathematics, Painting, and Printmaking. She is interested in making, seeing and reading on the visual arts and fond of creative writing. She has published exhibition reviews in the Anandabazar Patrika.