Unlike any other art form, theatre is never the same from one day to the next, for it is created and destroyed and created once again in each moment of its staging despite all the same variables: script, dialogues, stage, actors, sound, and light. For the people behind each of these don’t remain quite the same from one day to the next with the time that passes in between, as don’t the viewers. It is never quite the same production I am viewing despite choosing to watch each of the productions a few times over when I have been engaging with theatre. Each time I watch a production, I am left wondering how it is that one documents these individual moments that make up the experience of watching a production. How does one document an art as alive and spontaneous as theatre? My question draws itself from Rancière’s reading of aesthetics as ‘a specific regime for identifying and reflecting on the arts: a mode of articulation between ways of doing and making, their corresponding forms of visibility, and possible ways of thinking about their relationships…’ (Rancière 2004, 10).

This has been a recurring question as I watch yet another old and new production in this city. The overwhelming desire is to record the experience beyond sensory constraints. However, that often concludes in reductive ends in terms of what the documentation can offer. This has led to an immense gap in how theatre is experienced, studied, archived, critiqued and memorialised, barring some exceptions. Until the language of recording itself can be reimagined to set it free from its narrative trappings, theatre documentation most easily stumbles into those gaps—time and time again. Here comes the ongoing exhibition, In a Cannibal Time: Photographs by Naveen Kishore, which births a different language in his recording of theatre, marking a decisive intervention therein. These works, however, he maintains, are not documentation but recording of a time and art as he sees it. And perhaps, there lies the intimacy of what we see in his theatre photography, for it breathes an entirely transformative visual repertoire.

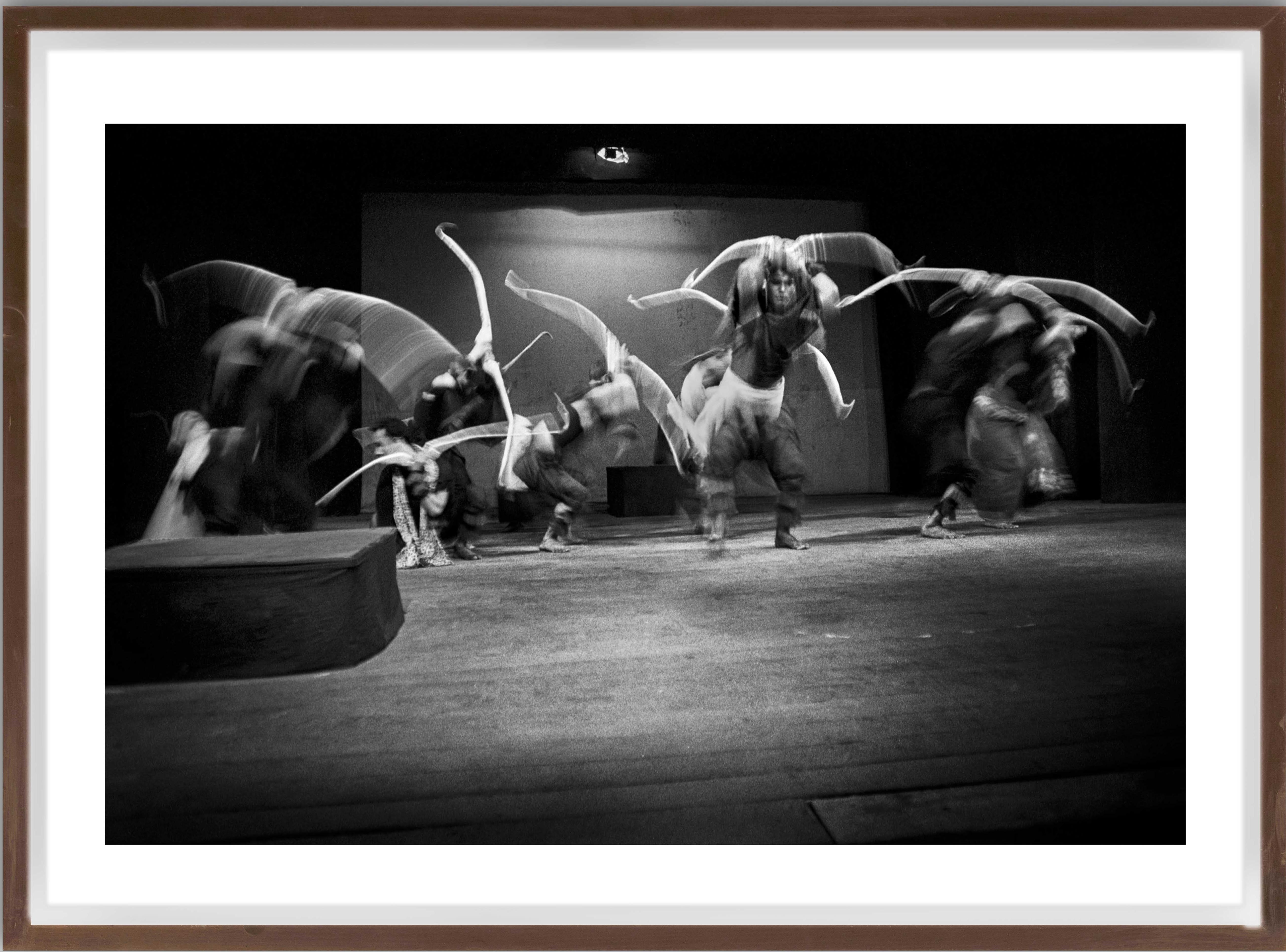

The show combines photographs from four significant bodies of Kishore’s work: Performing the Goddess, The Green Room of the Goddess, The Epic and the Elusive and In a Cannibal Time. Two direct representations of theatre as he sees it: Performing the Goddess and The Epic and the Elusive. While the first one brings forth a distinctive intimacy as he follows an individual theatre artist, Chapal Bhaduri, closely through his life in jatra as also its intersections and departures with his personal reckoning with gender and performativity, The Epic and the Elusive has a different air which grows out of a sort of anonymity of the performers as much as Kishore’s own experience of photographing Manipuri experimental theatre across years of extreme political violence in the 1990s. Crucially, the language in which this theatre was being performed was alien to Kishore. I would think that itself sets his recording of this theatre free from its primary tangible narrative constraints, for his experience of the theatre also falls outside the purview of a regular theatre discourse where dialogue is produced and received in certain moments. Here, I must emphasise that these photographs were part of a larger project called the Seagull Theatre Quarterly [STQ]: a seminal theatre journal developed by Naveen Kishore and Anjum Katyal, running between 1994-2003, that locates the socio-political context in which these photographs came to be conceived. The editor, Anjum Katyal, writes of STQ Issue 14/15: ‘The central focus of this issue is the experimental theatre that, in the early 70s, emerged as a strong presence, emphasising the exploration of traditional forms, reshaping techniques, themes and training methodologies, often incorporating thang-ta (the martial arts form of Manipur), and folk and classical dance.’

The blurs have a substantial presence in this particular body of work when viewed alongside the three other series on display. The intensity of movement is striking; therefore, much reflective of the time and space amid which this theatre was being performed as an attempt to find a vocabulary to respond to the violence that shook the state with devastating clashes between militancy and insurgency and the people of Manipur caught in between. Each of the frames brings an ever-present reference to Kishore’s life in the theatre with the blurs, swirls, shadows, light and dark—and maybe that is what creates the possibility of this reimagined language towards documenting theatre, otherwise so hard to articulate that people succumb to age-old tropes. As the curator, Ranjit Hoskote would argue: ‘This is pure theatre, celebrated by a camera unconstrained by conventional pieties of focus and framing.’

Theatre is urgent and immediate in a way that few other art forms are. It works as a collaborative force between the viewers and the performers in every moment of its expression. It is possible for the same reason that theatre has found such a diverse range of expression and experience from proscenium to street. And it is, therefore, no surprise that most authoritarian regimes have found their initial mediums of resistance emerging from the sphere of theatre. Theatre possesses immense scope in its ability to unite people within its fold. India has had a vibrant scene of political theatre historically from times of British colonialism towards an imagination, articulation and assertion of indigenous resistance, particularly heightened during moments of rupture historically—with the birth of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, Jana Natya Manch to theatre practitioners like Vijay Tendulkar, Utpal Dutt, Badal Sircar, Safdar Hashmi, Heisnam Kanhailal, to only name a few.

There has been an urgent need to record theatre—to document it. And yet, the question that haunts is: How does one record theatre without reducing it to its bare bones? A lot of what happens in theatre is in the experience of watching a production in a particular setting with a set of people forming their own simultaneous dialogue with the play and the existence of those parallel conversations intersects in building a larger discourse. While there has been an immense proliferation of video recordings of theatre from National Theatre, Broadway to West End and just as much closer home with Bengali theatre, one is often left wondering what these recordings have to offer by way of theatre production. How much of the politics of consuming and producing theatre is forgotten in this transition? Does the distinctive language of theatre find any space in these recordings for how much is lost in translation?

A sustained engagement with theatre calls for an expansive understanding of documentation. Dialogue around the historicity of the space and time of its performance, wherever that be, is an inescapable necessity. For instance, when talking about the history of theatre in Bengal, which is inevitably a history of left-leaning experimental theatre, where is the departure between the group and commercial theatre? Why is there one at all? What became of the more traditional form of theatre that was in practice in the rural parts of the city in the form of jatra? Why were the best of theatre practitioners of this time, but Soumitra Chatterjee, who almost single-handedly rebirthed the commercial theatre scene in the Hatibagan theatre para in ways that would ensure that the Bengali intelligentsia interacts with these spaces, unable to create meaningful dialogue between the group and commercial theatre instead of reducing them to being inherently contradictory? Why did Bengali group theatre refuse to recognise the towering and absolute presence of a theatre practitioner like him for the longest time? Why does a certain area in the north of the city, Hatibagan-Shovabazar, create the circumstances for a kind of theatre to thrive without being particularly wealthy? What political climate perpetuated the need to create a distinctive theatre repertoire? Who were the people performing in these times, and what kind of theatre were they bringing to the people? What logistical constraints were imposed on the creation and practice of this medium? Were the different theatre groups in conversation with each other? Did those conversations birth alternative imaginations for the medium? How do we read the spaces of these older theatre houses in the north, like Star, Minerva, Circarina, and Rang Mahal, and their fate into oblivion’s loss today? What moment in history brings yet another break in this landscape whereby now the theatre scene in that same area is dismal, to say the least, with all of it being confined to the wealthier parts of the city today?

Theatre documentation, therefore, cries out for active reimagination whereby the socio-historical context of its embodiment frames the conversation for what we see when we see and how. This, therefore, leads me back to Rancière’s (2004, 10) politics of aesthetics in ‘defining the connections within this aesthetic regime of the arts, the possibilities that they determine, and their modes of transformation…’. Rancière understands artistic practices as ‘“ways of doing and making” that intervene in the general distribution of ways of doing and making and the relationships they maintain to modes of being and forms of visibility’ (Rancière 2004, 13). It is precisely in this vein that I read Kishore’s theatre photography which intervenes into our sense perception of theatre so fundamentally that it produces possibilities of a new language for theatre—both as part of lived experience and a historical source.

Works cited:

- Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. London: Continuum.

- Katyal, Anjum. 1997. “Editorial.” Seagull Theatre Quarterly (14/15).

AUTHOR PROFILE

Rajosmita Roy is a PhD scholar of History interested in the history of modern South Asia, imperial, and gender history at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, funded by the SOAS Research Studentship. She is also a contributing editor for the Journal of The History of Ideas blog.