“Photographs bear witness to a human choice being exercised in a given situation. A photograph conveys: ‘I have decided that seeing this is worth recording.’ However, while recording what has been seen, a photograph always and by its nature refers to what is not seen. It isolates, preserves and presents a moment taken from a continuum. A photograph is effective when this chosen moment contains a quantum of truth.”

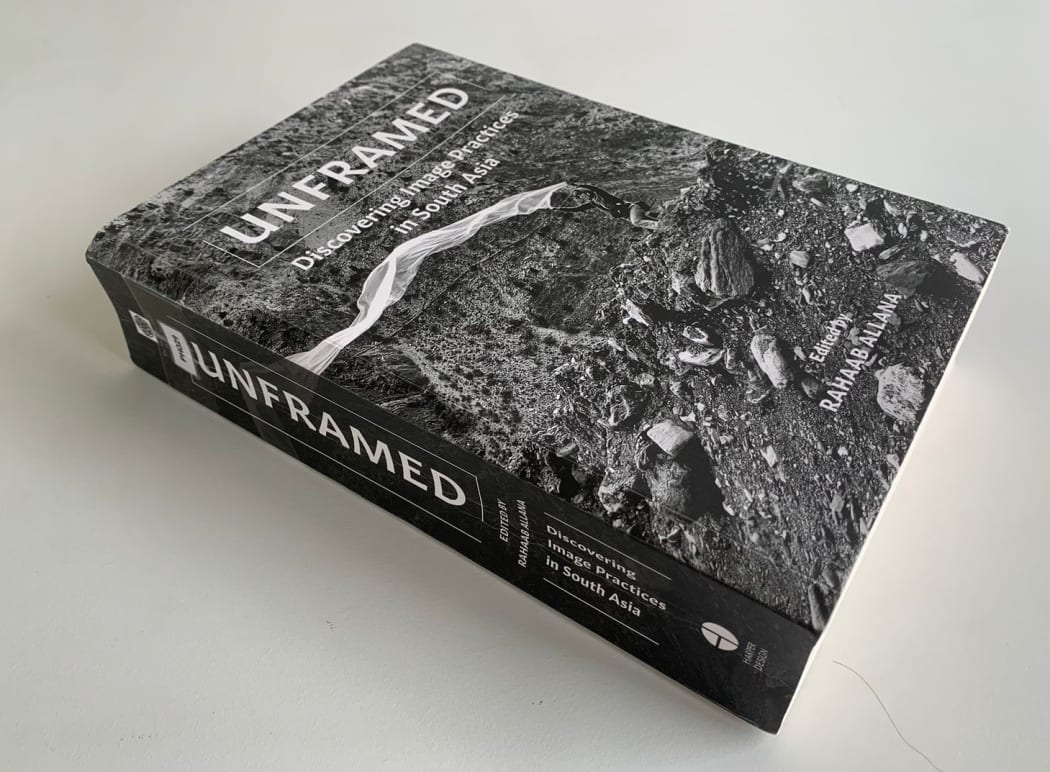

These lines by John Berger in Understanding a Photograph (Penguin, 2013) shed light on the inherent primal nature of all lens-based practices ever to exist. The marvellous publication by Harper Design that came out at the beginning of this year, Unframed: Discovering Image Practices in South Asia, hammers Berger’s idea by turning a critical eye to show how lens-based practices in the country are merging lyrical and evidentiary frameworks to break down our stereotypical and conditioned habits of viewing an image. Through its nuanced treatment of the historical and cultural contexts that have shaped photographic practices in South Asia, Unframed explores the subtle intermingling of memory and space, notions of selfhood, the modes of gaze, the blurring of geographic taxonomies, forms of identity and the unstable politics embedded in practices of image making over time. Deviating from the mainstream, it provides a comprehensive overview of the colonial and postcolonial influences on photography in the region, highlighting the complex dynamics of power, representation, and identity.

The editor of Unframed, Rahab Allana, is known for his contributions to the South Asian study and for promoting photography as an intrinsic art form and cultural practice. He served as the Curator of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in New Delhi, India, which is well-regarded for its efforts to preserve and promote the heritage of Indian photography and visual culture in many ways. Allana works nationally and internationally with museums, archives, cultural initiatives and institutions, universities and festivals. South Asia is a sensitive territory to deal with for any practitioner since, for the past many decades, it has evolved into a divided entity with emerging borders ‘gauged into the decolonised landmass with rival nationalist agendas’, as Rahaab Allana puts it in the introduction to the volume.

Time Changes, Imran Qureshi, 2008,

Courtesy: Imran Qureshi and Corvi Mora, London

The volume is divided into five distinct sections with thirty-one pieces under them. The sections successfully portray photography as a fundamental medium that can take up a hybrid form and, more importantly, as a socio-historical resource which expands our understanding of artistic engagement in colonial and post-colonial South Asia. The ensemble of texts by researchers, authors, theorists, curators and photographers from different generations explores the nuances of spatiality. The first section of the book studied the ideas of self and the Other by throwing light on the different layers of gaze and the rupture of identity. The careful editing by Allana enabled Unframed to scrutinize the intersectional dimensions of lens-based practices in South Asia. The third section of the volume effectively unpacks how photography has been used as a tool of both oppression and resistance, shedding light on the intricate interplay of politics and visual culture. The essay by Rahul Roy takes us through layers of reception, marking out the discrete geographies of the ‘fictional’ and the ‘documentary’.

One of the most commendable features of the book is its interdisciplinary approach. Drawing upon diverse fields such as art history, media studies, anthropology, and cultural studies, the essays collectively construct a comprehensive framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of image production and consumption in South Asia. This interdisciplinary perspective not only enriches the book's analytical depth but also highlights the interconnectedness of various image practices across the region over different time periods. The conversations and interviews with stalwarts like Shahidul Alam, Tanzim Wahab, Dechen Roder, Sai Htin Linn Htet and Nathalie Johnston probe into the traditional but effective way to seek common ground between different photographic genres through the analysis of the multifaceted and complex entity of South Asia.

Miss Buchwa Jan, Karachi, Rewachand Motumal & Sons, Karachi, c.1905,

Courtesy: Collotype

Transnationality looms large over the array of writings featured in Unframed, highlighting collaborations of artists across countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar. They provoke an insightful examination of various photographic genres and traditions within South Asia, including but not limited to portraiture, photojournalism, and fine art photography. A sensitive reader can navigate the regional variations and distinctive characteristics of these practices, following their evolution over time. The inclusion of numerous case studies and visual examples adds depth to the analysis and allows readers to connect theoretical concepts with real-world applications and not view the volume as a repository of vague jargon.

In addition to historical and cultural contexts, the book delves into the technological advancements and innovations that have shaped South Asian photography in recent times. The second section of the book deals with the impact of digital photography, social media, and globalisation on the production, distribution, and consumption of images in the region. This perspective acknowledges the contemporary relevance of the subject matter and its potential future trajectories. By examining how these technologies have transformed image production, distribution, and consumption, the book maintains its relevance in the context of the ever-evolving digital age. In the first article of the fifth section of Unframed, Nancy Adajania contextualised the Triennale India experiment, a state-organised periodic exhibition of world art, within the wider understanding of culture in the decades after Indian independence as a subject arising from the country’s self-image.

Two Girls; by Golam Kasem, 1927, B2 sized glass negative

Courtesy: Golam Kasem/ Drik

Unframed does not shy away from addressing critical questions related to ethics, representation, and power dynamics in image practices. The role of images in political and social movements, the itinerary of themes of unaccounted emotions and collectivism in art feature in the fourth section of the volume. These discussions provide a thought-provoking and ethical dimension to the book, encouraging readers to reflect on the responsibilities and implications of image-making. The photographs, often haunting and disturbing, attached to each article become the window to gauge the depths of the ideas talked about in the pieces. In monochrome, sepia tone and coloured photos, both vintage and modern, the reader finds adherence to the discourses incorporated in Unframed. Undoubtedly, this remarkable anthology restages the holistic history of photography in South Asia and reinvents the field in foundational ways by exploring the trans-regional aspects of the same.

Srilagna completed her education at the Department of History, Jadavpur University. She is a practising researcher, archivist, avid reader, and animal lover.