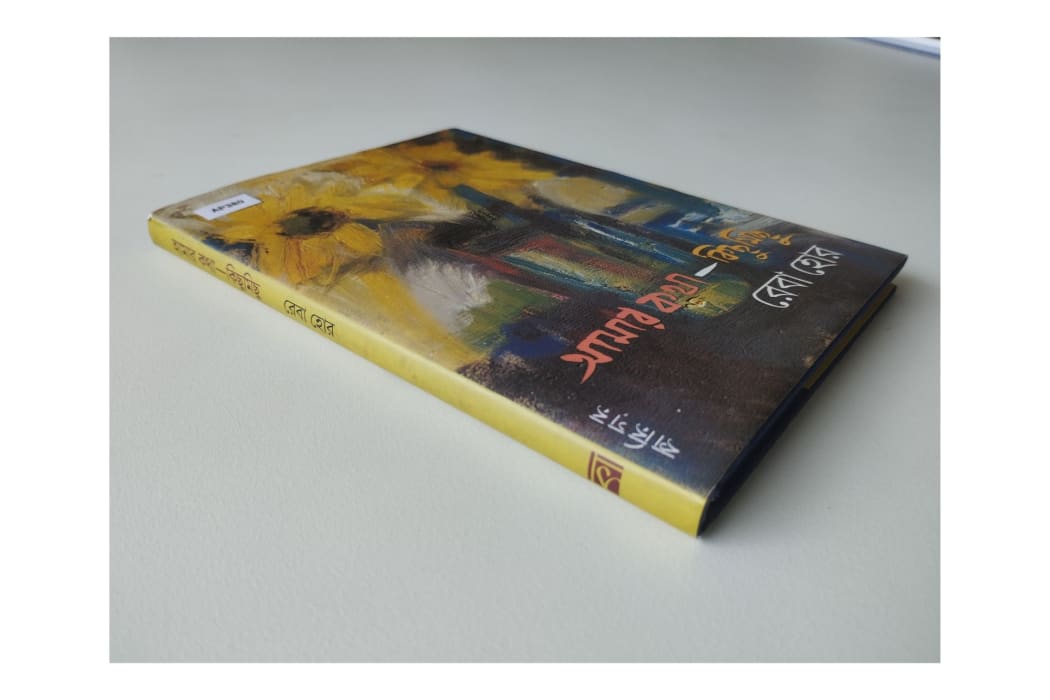

Author: Reba Hore

Dimension: 7 X 5 inches

Type: Hardcover

Number of illustrations: 17

Publisher: Karigar

Number of pages: 82

‘Who am I?

Well, I am on a journey to be a wholesome human being, consisting of virtues and flaws alike. Sometimes intentionally, sometimes in oblivion.

Don’t know if I could succeed. Can’t be too sure of it. Can I?’

‘Amar Katha- Kichhu Michhu’, published by Karigar in 2016, is the heartfelt memoir of Reba Hore, the prolific 20th-century artist and activist. The opening lines of the book expose us to one of the pivotal themes of it- self-reflection- something that every person has to deal with at some stage of their life. Working as a vivacious painter, printmaker and sculptor, Reba Hore developed a uniquely instinctive idiom of expression throughout the decades she worked.

From the political upheavals of mid-20th century Calcutta, student life at the Government School of Art and Crafts and the growth of artistic styles in parity with changes in places of residence, the artist’s narrative covers a plethora of significant affairs and sentiments. Most of Reba Hore’s works are driven by intuitiveness and stem from her experiences and interactions. Predominantly composed of bold animated brush strokes and frenzied energy, her paintings create a lively mesh of emotions aided by the free-style use of hues. Just like her artworks, her emphasis on simplicity, honesty and vital sentiments have been delicately expressed in the pages of her memoir. She states:

‘I have allowed my paintings to gain their own flow from my lived experiences. Medium and materials come later. My artworks are a result of my conscious and subconscious efforts. This will stay till my very last days because this is a key element of my personality.’

Illustration by Reba Hore in ‘Amar Katha’, Karigar Prakashani, 2016

In ‘Amar Katha’, Reba Hore narrates her childhood memories, analysing her father's dominance in the household and the omnipresent influence of her mother on herself and her siblings. After graduating in Economics from Asutosh College, the artist proceeded to take her lessons in painting at the Government School of Art and Crafts. Her favourite classes were life classes and wood engraving. Becoming a member of the Communist Party in 1948 shaped a core arena of her student life. She and her friends drew posters, cartoons, placards for the rallies, and party propaganda. Owing to the narrowmindedness of some leaders and the internal degradation of party principles, her enthusiasm faded after a few years. She mentions how the presence of her friends, beloved acquaintances and family members always performed as a shield against the bitter realities of life. In her narrative, Reba Hore does not shy away from criticising the activities of political groups, leaders or individuals and studies her daily experiences in a vehemently feminist light. Her emphasis on the strength of female friendships during her college years and the gender dynamics amidst the art world in her later life pronounces her advocacy of strong feminist ideals. She actively took part in political movements in college; the artist has recollected one such anecdote in the memoir:

“At that time, the movement in the Art School was raging to demand hostel accommodation. The students, the poor boys who used to come from faraway suburbs, used to have great difficulty in accommodation. Many boys came from lower economic classes, and low-cost food and shelter were essential to continue studying. The matter was continuously being ignored and suppressed by the authority. So, under the leadership of the Union, all the art school students marched to the Writers’ Building. They sat there all day, waiting and demanding to meet the minister. Girls were drawing on the streets with chalk. The next day, Statesman reported, ‘Boys shouting slogans and girls drawing cartoons!’ We laughed about it so much! After a few days, authorities finally arranged for hostel accommodation.”

In lucid and simple Bengali, Hore narrates her teaching experiences at St. John’s Diocesan School (Kolkata) and Spring Dales School(Delhi) and her domestic encounters with neighbours and families of landlords in their rented rooms. She used to enjoy the company of children thoroughly and believed that art becomes truly free in kids’ hands. Flipping through her narrative, one can notice the depth of the artist’s core values about life, love, art and empathy. Comparing the art worlds of the 20th and 21st centuries, Hore emphasises how the increasing prioritisation of money is eroding away ethics and principles. While the memoir showcases the strength and vitality of Reba Hore’s personality, it also highlights the importance of love, effort, sympathy and dedication to live a fulfilling life.

The last section of ‘Amar Katha’, titled ‘Reba Hore 2009’, is an interesting compilation of some rhymes and sections of prose poetry by the artist. This segment is mostly a soliloquy, where the artist unleashes her intense thoughts about the life of solitude and the effect of that on her art. The volume is blessed with seventeen exuberant artworks of Hore: dark and shadowy forms of men and animals crowd these drawings amidst the play of light and darkness. Huddled together in intermingled gestures, the figures attain abstraction as the shapes become somewhat misty. Energy and emotions ooze out of each of these artworks unmistakably.

In much of her artistic career, despite creating a large volume of artworks over various mediums, Reba Hore has largely lived under the shadows of her more renowned artist-husband, Somnath Hore. She could witness only a couple of solo exhibitions and some joint shows with her husband (Chourangi Terrace, Calcutta, 1954) during her lifetime. Often, their works have been illogically compared without keeping in mind that Somnath and Reba were artists with very different painting styles. Besides, we often tend to overlook the social contexts and inherently gendered dynamics that prevailed during the artists’ lifetime. ‘Amar Kotha’ is a testament to Reba’s lifelong struggle and encourages us to break away from the notion above and inspect her works in a new light.

Srilagna is an art and culture buff who is interested in the public history of South Asia. She is a part-time researcher and archivist, full-time foodie and animal lover.